No money, no lime: Restoring ancient Italian walls on a shoestring

John Heseltine

Where to begin...

By June of 2024 the roof was finished and I had fully recovered from my accident, so it was time to tackle the next of the big problems, the condition of the walls. The heavy building work had gone really well, the floors were in and the roof was fixed, but the plaster was a real mess.

There were areas missing because of the building work, and areas damaged by rain pouring down the inside of the walls and separating the plaster from the masonry (this is called "blown plaster"), plus all sorts of holes and cracks — so, lots of problems.

The damaged plaster was not just a technical problem; it was an aesthetic and financial one as well.

In a situation like this, the normal builder's approach would be to remove all the old plaster, put on a flat base coat to smooth over the bumps in the wall, and then apply a new top coat of fine plaster — resulting in flat walls with none of the lumpy finish that you get from old lime plaster.

So the situation was this:

Stripping off all the old plaster and replastering the walls would be very expensive in terms of both manpower and materials, and it would take more time than we had available.

Plastering with lime is not a quick process — the plaster can take up to a year to fully harden — and time was one of the things I didn’t have. I was up against the commune's deadline to finish the renovation.

Our bank account was empty again. All our money had been spent doing the roof. So whatever I was going to do needed to be simple, quick, and low-cost.

If the damaged areas were replastered using standard modern methods, the result would look strange, because the new parts would be flat and the old parts would not.

I actually preferred the lumpy old-fashioned lime plaster finish to a modern dead-flat one; I just thought it looked more interesting.

To be honest, I didn’t really have a clue what I was doing, and I was pretty much making all of this up as I went along. I had a vague idea of where I wanted to get to, but no idea how to get there.

Fortunately, I got some excellent advice from a very good local plasterer, who pointed me in the right direction. He introduced me to a building supply company called Fassa Bortolo — it's a company you will probably be familiar with if you’ve spent any time in a builders' yard in Italy.

Fassa Bortolo makes a wide range of pre-mixed cements, mortars, and renders — basically everything you might need for finishing, sticking, and filling when building walls.

According to our local plaster, I needed to get the following materials:

M30

M30 is a premixed general-use mortar used for fixing rock into place and for general repairs. It saves you from having to buy the separate ingredients and mix them yourself. It already has the right proportions of sand and aggregates, lime, and cement.

KD2

KD2 is a bit more specialised. It does what the old lime-based first-coat plaster used to do. It’s an interesting mix of aggregates, lime, a small amount of cement and, I think, long-chain polymers (this is a guess on my part). The result is a plaster that has a gloopy, cake-mix sort of texture. KD2 is sticky in a way that normal cement-based mixes are not.

The other great thing is that it can be worked into shapes, and you can build up thick layers very quickly. It is primarily a lime-based mix but with enough cement for it to harden slowly, which — as I will explain later — can be incredibly useful.

You can probably now see where the texture and shape of our walls came from. I think they were plastered by throwing on a thin lime mix, building it up in layers, and then smoothing it off with a stiff brush. The undulations in the surface reflect the lumpiness of the underlying rocks.

My theory is that once enough base coat was on the walls to flatten them out sufficiently, they were finished with a top coat of stronger plaster, which was mixed with sand and applied with a brush. I know I'm right about the brush, because I can still see bristle marks in the finished plaster.

Perfectly lumpy walls...

The underlying wall is far from flat — it’s lumpy because of the rocks used to build it.

These days, plastering tends to be nearly always done with a flat trowel. And plasterboard and render spraying mean you can now pretty much give any wall a smooth, even finish if you have the equipment. We’ve got very good at making walls flat.

But it hasn’t always been like this. You can’t stick material to a lumpy wall using a flat plastering trowel. Where the rocks stick out, the plaster will be very thin; where there are gaps between the rocks, there will be a thick layer of plaster that will fall out because it’s too heavy. So how did plasterers put the base coat on?

Below is a training video showing how to apply lime render to an uneven wall. You don’t smooth it on with a trowel; you throw it (watch from the 2:45 minute mark).

Take a look at this random section of wall from the house.

The surface is rough and uneven and covered in undulations. This plastering was obviously not done with a flat trowel.

Now look at the underlying wall.

...and how to get them

I went over the walls, securing loose stones and filling any voids with small rocks fixed in place with M30.

Each room, on average, took about five days of preparation: I knocked off loose plaster, made sure whatever was left on the wall was solid, and raked out all the cracks.

Then, working with my friendly expert plasterer, we began plastering, using the technique I described above. First, the plaster sealed the uncovered areas with a thin mix of KD2 by throwing it at the wall. The result wasn't flat, but it was certainly a more even surface than the original bare rock.

Once enough KD2 had been applied in this way, a final layer could be applied quite roughly with a short trowel. At this stage, you don’t need to be too careful, because this is not creating the final surface — that comes later.

Next comes the clever bit. KD2 takes a long time to harden. You need to leave it until it’s still soft enough to work with but hard enough not to come off the wall.

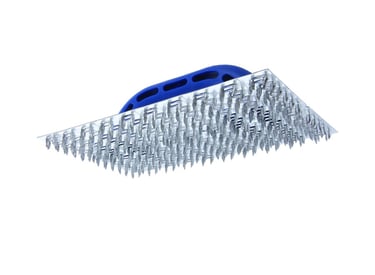

And then you use one of these:

This is a raschiatore intonaco. I’m not positive, but I think builders in the UK call it a “devil’s trowel,” which sounds a lot more sinister. It's a kind of rasp — designed not to put material onto a wall but to take it off. A raschiatore intonaco is covered in hundreds of sharp spikes, and when you use it to rub the surface of the KD2, it takes the excess off like a big Parmigiano grater.

The plasterer showed me how to use this tool and, toiling late into the night, I worked to flatten and shape the new wall surfaces to match the old plaster as soon as the KD2 had became hard enough to deal with.

Leave it too long, and you’re in for a really hard day’s slog doing what you could have done in 15 minutes if you had timed it right. (I speak from experience — you only make this mistake once.)

This is how the room looked when I'd finished the base coat of KD2.

Finishing

At the end of this process, all the KD2 base coat had been applied and shaped by hand, and no more rock was showing. But the walls were nowhere near finished.

I had to work out a way of getting the new KD2 to match the texture of the old parts of the wall.

The first thing I tried was painting a patch of it to see what it would look like. I might as well not have bothered. KD2, when dry, is like a super sponge — if you try to apply paint to it, it’s just sucked into the surface.

I tried plaster, but the KD2 sucked every last drop of water out of it and then it fell off. I tried adding a sealant, but it made no difference at all.

Even where a little paint had managed to stick, it was still obvious that the KD2 had a completely different texture to the rest of the wall.

So I went back to the old walls and had a good look at them. They had a very distinctive finish, which had clearly been created with a brush. I decided to try something similar.

There's another material that plasterers often use here that I thought might work. It's a Fassa Bortolo mix called A64.

A64 is a gritty traditional lime-based finish, and you’ll see it on walls all over this part of Italy. I’m not sure why it contains grit — and no one has been able to explain it to me — but I like it, and it’s very nice to use. It also contains shredded glass fibres, which give it flexibility and strength. It goes on smoothly, sticks well, and can be worked using a normal trowel, sponge, or soft float.

I decided to give A64 a try.

I soaked a section of the wall with water until the KD2 base couldn’t absorb any more. Then I mixed a bucket of A64 with a lot of water until it was like batter. I painted it onto the wall and let it dry.

This worked. It still didn’t have the exact same texture as the original walls, but it was getting closer and at least I was heading in the right direction.

Once the wall was completely dry and sealed, I mixed up another bucket of A64, this time thicker — halfway between plaster and paint — and then, using a very stiff brush, a small trowel, and a sponge, worked it into the surfaces, blending the old and the new. I sprayed on water to keep it wet where needed and used a mix of different brushes to get the finish I wanted — it was more art than plastering.

After a lot of experimentation and practice, I got it right — or as right as it was going to get. I then continued around the house, finishing all the bare KD2 walls with A64.

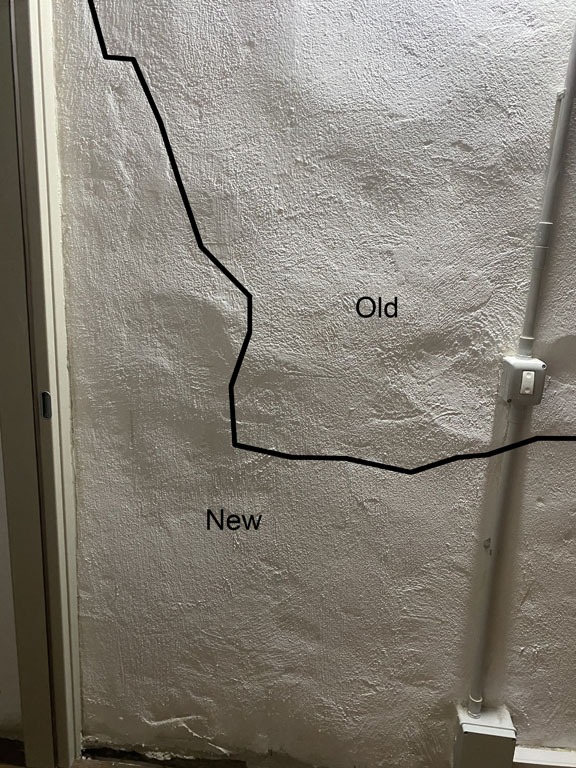

You can judge the results for yourself: the two images below are the same, but on one I’ve drawn a line between where my new plastering ends and the old wall begins.

Not perfect, but pretty damn good. I truly doubt that anyone in the house looking at these walls would spot the difference unless it was pointed out.

And this is how the finished walls look. The paint is a bit patchy because Italian paint is made with a lot of lime, so it takes time to react with the air before it goes white. The first time I used it, I thought I had been sold a dodgy tub of paint, because it goes on like watered-down milk. But overall, I’m pretty pleased with the result.

I managed to save a lot of the old plasterwork. Overall, the plastering work cost me a fraction of what it would have cost to re-plaster the whole house, and I think it looks pretty great.

Job done.